HISTORIEK HISTORIQUE HISTORIC

- Welcome

Accueil - Nieuws

Nouvelles- 28/12 UK to check ‘shadow fleet’ tankers for ‘suspect, dubious’ insurance during English Channel transits

- 31/12 Transpetro to use Marlink’s VSAT + Starlink hybrid solution on 26 tankers

- 01/01 U.S. Sanctions Fail to Stop Chinese Power Plant, Delivery Salvages Next Stage of Russian Arctic LNG Plant

- 03/01 India’s Oil Demand Drives CMB Tech Fleet Diversification

- 07/01 World’s Oldest Shipwreck Is at Dokos Island, Greece

- 09/01 Port Oostende Fights to Preserve Critical RoRo Shipping Route.

- 11/01 LNG bunkering poised for a bright future

- 14/01 Russische driemaster Shtandart nergens welkom, kapitein wacht met smart op coulance van Brussel

- 16/01 Russia resells more gas in Europe after cutting off Austria, sources, data show

- 21/01 EU Closes in on More Tanker Sanctions to Enforce Russian Oil Price Cap

- 23/01 Black swan events keep container lines shipshape

- 25/01 As war blocks Russia, China boxes take Middle Corridor

- Kalender Calendrier

- BML Nieuws

LMB Nouvelles - Historiek

Historique- 18/11 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (I)

- 25/11 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (II)

- 08/12 Een beetje geschiedenis (I)

- 15/12 Een beetje geschiedenis (II)

- 21/12 Een beetje geschiedenis (III)

- 29/12 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (III)

- 05/01 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (IV)

- 12/01 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (V)

- 19/01 De schipbreuk van de kotter Princess of Wales en de schoener l'Aventure (VI)

- 26/01 Gamming Chairs and Gimballed Beds: Women on board 19th-century Ships

- Dossier

Dossier

- 27/12 Dirty-to-clean switch caps high LR2 tanker freight rates as supply widens

- 30/12 How SECNAV’s claims about S. Korean, Japanese shipbuilders do and do not line up

- 02/01 Why do ships ‘zig’ when they should have ‘zagged’?

- 04/01 Namibia to rival Guyana as world’s newest oil and gas hotspot following massive offshore discoveries

- 06/01 Zenobe Gramme

- 08/01 How SECNAV’s claims about S. Korean, Japanese shipbuilders do and do not line up

- 10/01 Ocean container shipping market reaches a tipping point

- 13/01 La révolution culturelle chez Maersk, les revirements et autres effets de panique

- 15/01 Sharing tussles over major sea route worry exporters

- 17/01 Somali piracy: It's more sophisticated than you thought

- 20/01 Containership and port operators face a host of issues as peak season arrives

- 22/01 Pioneering Spirit picks up the reins for GTA deepwater pipelay

- 24/01 'Dark fleet' of oil tankers risk more maritime disasters in Asia

- Raad

Comité - Verenigingen

Associations - Contacten

Contacts - Links

Liens - Boeken

Livres - Archives

Archieven- Archieven 1 - Archives 1

- Archieven 2 - Archives 2

- Archieven 3 - Archives 3

- Archieven 4 - Archives 4

- Archieven 5 - Archives 5

- Archieven 6 - Archives 6

- Archieven 7 - Archives 7

- Archieven 8 - Archives 8

- Archieven 9 - Archives 9

- Archieven 10 - Archives 10

- Archieven 11 - Archives 11

- Archieven 12 - Archives 12

- Archieven 13 - Archives 13

- Archieven 14 - Archives 14

- Archieven 15 - Archives 15

- Archieven 16 - Archives 16

- Archieven 17 - Archives 17

- Archives 18 - Archieven 18

- Archieven 19 - Archives 19

- Photos

Foto's

Gamming Chairs and Gimballed Beds: Women on board 19th-century Ships

Abstract

On the Charles W. Morgan as on most whaleships, the captain’s wife lived in only four cabins between decks: stateroom, sitting, dining salon and pantry. With her husband, she shared a stateroom situated aft, on the starboard side. Besides the bed, their cabin contained small closets and drawers, with space for a trunk to be nailed to the floor. Their personal head (toilet) opened aft of the cabin door. A narrow sitting room along the transom provided a separate space for the captain and his wife to entertain visiting guests (Brewster and Druett 1992). Forward of this, the dining salon was located from which a companionway provided access to the deck. Under a skylight, a large table with rails designed to keep the dishes from sliding off, was bolted to the sole. The captain’s wife shared the dining room with the officers and steward, who slept in cabins along one side. On the forward bulkhead to starboard, a door led to the small pantry where she prepared food and mixtures such as bread dough for the cook to bake in the galley (Druett 1998:136). On deck, a captain’s wife stayed aft out of the way of the crew work or she could also retreat to the top of the hurricane house, a roofed structure that wrapped around the stern on whaleships (Crapo 1866).

Captains’ Wives

In all, five captains’ wives sailed on Charles W. Morgan, but only three of them will be included here in the descriptions of the large objects considered associated with these women on the ship. The three wives who sailed on board during the latter half of the 19th century were as follows: Lydia Goodspeed Landers (1864-1867), Clara Tinkham (1875-1876), and Honor Matthews Earle (1896-1904). The primary documents about these particular women come from several sources including sailor’s journals, newspaper articles and letters. For Lydia, the first mate, Charles Chase, wrote a journal of the voyage in which he mentioned her, and similarly for Clara, sailor Charles Willis wrote of the voyage. Both Clara and Honor were interviewed for newspapers, and Honor’s son, Jamie Earle, wrote letters in which he reminisced of growing up aboard Charles W. Morgan. Secondary sources by maritime historians Joan Druett, John F. Leavitt, and Lisa Norling provided direction for the research.

Gimballed beds

Lydia Goodspeed Landers, the first captain’s wife on Charles W. Morgan, married Captain Thomas soon after the death of his first wife. In 1863, the ship sailed out around Cape Horn without Lydia. Possibly because the ship owners disagreed with the practice of taking wives to sea, she travelled cross-country to meet her husband in San Francisco (Chase 1867; Leavitt 1998:38). Although the archives at Mystic Seaport Museum (MSM) do not hold her journal, many wives wrote of their first experience as the only woman on board. “Now I am in the place that is to be my home, possibly for 3 or 4 years... it all seems so strange, so many Men and not one Woman beside myself... the motion of the Ship I shall be a long time getting used to...” (Williams 1964:3–4).

As a concession to her comfort, Lydia’s husband installed a gimballed bed in their cabin (Leavitt 1998:38). Gimbals function to keep an item level to the horizon despite the heel of a ship. Navigation relied on gimballed compasses in which two pivot points joined by rings supported the compass and kept the needle from grounding during heavy seas. Archaeologists found one of the earliest examples of a gimballing system during the excavation of the shipwreck

Whaling & Charles W. Morgan

As whaling voyages from New England became longer in the 19th century, captains’ wives refused to endure these separations, and began to join their husbands on board the ships. The change occurred as nearby whaling grounds in the Atlantic Ocean became fished out and whalers needed to hunt areas further away in the Indian and Pacific oceans taking four years or more to fill their holds with oil. The ship functioned as a processing plant, as the small boats chased the whales and dragged back their prizes. The slurry of blubber on deck, and the black smoke from the tryworks as they rendered it to oil, made for a messy business (Brewster and Druett 1992). Despite this malodorous, rough, and dirty situation, women still chose to follow their husbands to sea. “The Ship is the dirtiest place that I ever saw when they are cutting in and trying out whales. ... The smell of the oil is quite offensive to me” (Williams 1964:26).

The whaleship Charles W. Morgan made 37 voyages in 80 years after its launching in 1841. Though the whaling voyages ended in the 1920s, the ship still floats at Mystic Seaport (and hopefully will not be an archaeological site for many years to come). Charles W. Morgan, the owner of his namesake and investor in several other whaleships in the New Bedford fleet, noted that Captain Ewer’s wife would be accompanying her husband on the whaleship Emily Morgan. He wrote, “This custom is becoming quite common and no disadvantages have been noticed... There is more decency and order on board where there is a woman” (Morgan 1849: July 25). Morgan may have had some influence in policy concerning wives aboard the ships he invested in, but despite his opinion, it would be 14 years later and after he sold his ship before a wife sailed with a captain of Charles W. Morgan (Chase 1867; Leavitt 1998:38).

Arriving with only her trunk of belongings, a captain’s wife soon learned that space on board ship came at a premium, each square foot designated with a specific use. The main purpose of ships, to transport commercial cargo, meant that they were designed around the carrying capacity of the hold. Only the clipper ships built at mid-century sacrificed some of that hold space for speed (Crothers 2000). On a whaleship, the hold started empty, carrying only staves and metal hoops. During the voyage, they made these into barrels and filled them with oil to be stored. In the remaining space, those on board lived in compact quarters. The crew kept to the forecastle in the bow, and the officers spread out in slightly more room within the aft cabins (Deblois 1856; Druett 2001). The wife (and any children) of the captain joined him in the after cabins. Due to class segregation norms, their living areas were separate from the regular sailors (Norling 2000).

On the Charles W. Morgan as on most whaleships, the captain’s wife lived in only four cabins between decks: stateroom, sitting, dining salon and pantry. With her husband, she shared a stateroom situated aft, on the starboard side. Besides the bed, their cabin contained small closets and drawers, with space for a trunk to be nailed to the floor. Their personal head (toilet) opened aft of the cabin door. A narrow sitting room along the transom provided a separate space for the captain and his wife to entertain visiting guests (Brewster and Druett 1992). Forward of this, the dining salon was located from which a companionway provided access to the deck. Under a skylight, a large table with rails designed to keep the dishes from sliding off, was bolted to the sole. The captain’s wife shared the dining room with the officers and steward, who slept in cabins along one side. On the forward bulkhead to starboard, a door led to the small pantry where she prepared food and mixtures such as bread dough for the cook to bake in the galley (Druett 1998:136). On deck, a captain’s wife stayed aft out of the way of the crew work or she could also retreat to the top of the hurricane house, a roofed structure that wrapped around the stern on whaleships (Crapo 1866).

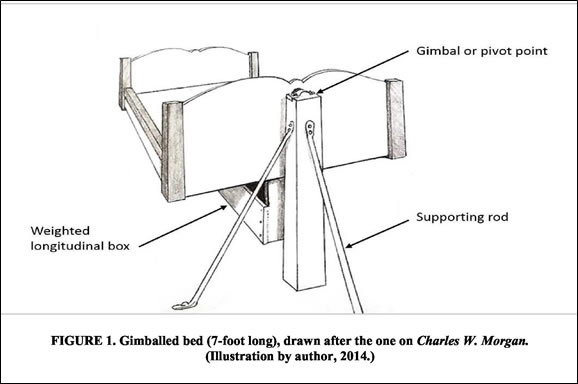

Mary Rose, sunk in 1545 (Marsden 2003). Both hammocks and swinging cots, precursors to the gimballed bed, pivoted on only the longitudinal axis. The canvas hammocks adopted by the Royal Navy of England in 1597 could be rolled up to clear space (Blomfield 191 1). Captain James Cook on Endeavour (1769-177 1) slept in a swinging cot that could be stowed during the day. Gimballed beds functioned by swinging between two posts, located at the head and foot. Made of wood and topped with a mattress, they remained in place regardless of time of day. A trough-like structure attached under the length of the bed held bricks or stones to dampen the motion even further (Figure 1).

Despite the added comfort, the trip seemed turbulent. Captain Landers’ son from his first marriage came along as cabin boy, but fell overboard from the rigging into the sea and was lost (Chase 1867). Soon after, Lydia went ashore at Guam to give birth to their son while the ship went on whaling. Her husband returned for her when the baby was only 3 weeks old and they named him Arthur after the son who had died. The mate’s journal tells of the captain’s short temper and incidents of discipline breaking down (Chase 1867; Leavitt 1998:41). The voyage lasted another 2 years and, the bed remained on the ship regardless of whether a captain brought his wife on subsequent voyages. Years later Jamie Earle noted his mother’s practiced ease of pushing her foot on the wall to free the bed from where it stuck after a large wave motion (Earle 1965; Druett 2001:125).

Gamming chairs

Clara Tinkham boarded Charles W. Morgan on a spring day in 1875. “The Ship looks large as we near it; we have reached her and the men have lifted me up the high side in an arm chair; quite a novel way it seemed to me” (Williams 1964). Gamming chairs are named for the event known as a “gam” of whaleships meeting at sea when unlike with merchant ships, they often stopped to exchange news and mail (Brewster and Druett 1992:282). If weather permitted, the officers and wives visited the other ship by small boat. To lift and lower a genteel lady over the side to her transport, sailors hauled the gamming chair with ropes slung by tackles from the yards or a boat davit (Figure 2). This allowed her to forego the challenge of climbing a ladder up the side of a ship (Leavitt 1998:38). These chairs were usually of wood, and on a whaleship, might be made by the cooper from a half-barrel and fitted with a seat (Deblois 1856).

A gamming chair from Charles W. Morgan still exists in the collections at Mystic Seaport (MSM Accession #1991.80), but no documentation exists as to the manufacture date of the chair. The artifact record notes: “used by Captain John Gonsalves on the Morgan's final whaling voyage in 1920-2 1 ” but more likely the chair lifted the wives of captains who visited him. Painted white with a canvas back, a photograph in the Mystic Seaport collections shows a toddler posed in it while the ship sat at a dockside museum at Colonel Greene’s Estate (MSM Accession #1983.99.28). The collection record describes the gamming chair as about 3.5 ft. tall, having four shackles attached to the base by thimbles and two ropes spliced for suspension from an eye where the lifting tackle would be attached.

The design of the chair kept Clara from the embarrassment of dishevelment in her fine visiting clothes, and safeguarded her modesty from any sailors that might see under her skirts as she descended from above them into the small boat. Unfortunately, the chair often spun around and dunked the occupant (Earle 1965) and the danger of falling in and drowning became a far greater concern under the weight of corsets and petticoats. When going for a gam, Honor Earle rode the small boat down as it lowered on the davits, refusing to use a gamming chair at all so its presence on the ship might be deemed insignificant (Earle 1965: Druett 2001:50).

Parlor Organs

Clara brought her parlor organ on the Charles W. Morgan, and probably located it in the sitting room, or against the aft bulkhead in the dining salon (Willis 1876; Leavitt 1998:46). The parlor reed organ, an instrument similar in looks to an upright piano, generated sound by the player pumping foot pedals while pressing the keys. This compact organ became fashionable in homes during the 1840s. Developed in the early 19th century, patents increased exponentially in the 1850s, and after the Civil War, the annual production of reed organs reached over fifteen thousand instruments (Ames 1992, Gellerman 1973). As production increased, cost decreased, allowing the middle class an affordable alternative to the piano (Ames 1992). In 1886, Mason & Hamlin Co. priced organs in their catalogue from $100 to $400. Often an ornate hutch (upper section), built with wood inlays and scrollwork, topped the cabinet that enclosed the inner workings. One feature of particular advantage to their use on ships, parlor organs kept their tune even in temperature and humidity changes (Waring 2002). Their popularity reached a high point in about 1890, and then declined in the beginning of the 20th century with the introduction of the phonograph, piano and eventually the electric keyboard (Gellerman 1973).

With the popularization of these instruments by the middle class, they came to signify the feminine, social status, religion at home. Contemporary trade cards advertising parlor organs portrayed these connections, showing women as the predominant players, images of wealth and therefore status of ownership, and ecclesiastical associations, such as the slogan of “Church, Chapel & Parlor Organs” on the Mason & Hamlin card. The organ and its music also symbolized civilization while abroad.

Journal entries on a ship often refer to singing shanties and playing small instruments such as concertinas and tin flutes, but bringing a parlor organ on board acknowledged the feminine in music. In Victorian times, playing the parlor organ became an “attribute of ladydom” for the middle class. Girls and young women took lessons to cultivate their role as the “genteel female” (Ames 1980:625). Women took pride in their accomplishment on the organ and singing with family. Hattie Atwood wrote, “I had taken some quarters of lessons on a piano, and so of course I felt perfectly competent to play most anything. So on this day father and I had a sing...” (Freeman and Dahl 1999:35).

The ownership of a parlor organ represented higher social status. The purchase of an organ by a family required a certain level of wealth to be able to afford it. As an expensive item that took up space and time, it created possibilities of “respect and deference” from neighbours (Ames 1992:160). The family made space for it in the parlor, and gathered around it with kinfolk and friends. Elaborate hutches included shelves on which the family displayed treasured objects and photographs as if on an altar (Ames 1980:623).

The sound of the parlor organ closely resembled a church pipe organ, hence the ecclesiastical associations of the artifact (Ames 1992:157). In religious observances at home in the 19th century, the wife performed the clerical duties including reading from the bible and playing hymns on the organ to instill “Christian virtues and values in the family” (Ames 1992:628). On board ships, women played the organ even on a Sunday, but refrained from the usual tunes, playing only “sacred music” for the Sabbath (Page and Johnson 1950:27).

In the 19th century, photographs of frontier life that included a parlor organ emphasized the connection to the former home and culture of the pioneers (Ames 1980:635). This concept can be applied to the isolation felt on a ship and bringing the reed organ on a voyage symbolized civilization and the community. In a remote place, the music played reminded those listening of home across the ocean, yet brought that feeling of home into the present, singing songs they once sang together with their family far away. Based on this symbolism, the organ represents several attributes that could make a woman feel more at home on a ship.

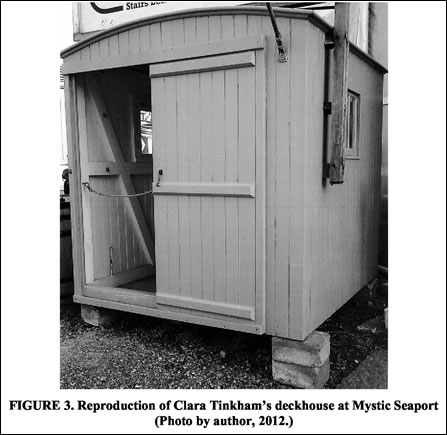

Little Deckhouses

The small deckhouse built for Clara’s comfort sat forward of the mizzen mast under the spare boat skids. The location might mitigate her seasickness, by allowing her a view over the stern. Compared to below decks, the improved ventilation might reduce the stench of whale blubber that could overwhelm the refined sensibilities of a captain’s wife (Druett 2001).

Until the 1850s, deckhouses seldom existed on whaleships. They kept an open deck plan to allow room for processing the whale blubber to render down in the tryworks, and for easy access to boat davits, raised anchor decks, and spare boat skids. In the last half of the century, the U-shaped, stern structure known as the “hurricane house” became a distinguishing feature of whaleships (Leavitt 1998:17). Sections of this house held a galley or storage, enclosed companionways to lower decks, and a head (toilet), and the other part roofed over the wheel to give the helmsman some shelter (Allyn 1972). All structures on whaleships served a practical function, with no embellishments.

On merchant ships, the large deckhouses, trunk houses, and underneath the poop deck accommodated cabins for officers, provided storage and included galley spaces (Crothers 2000). This arrangement allowed for increased cargo space below decks, and improved cabin conditions with increased light and ventilation. Great cabins afforded room for furniture such as walnut tables, side boards, stuffed chairs, parlor organs, and even fireplaces (Montgomery 1898). The massive SS Great Britain included a 1 00-foot long promenade below the skylights for first class passengers under the poop deck. Clipper ships furnished lavish accommodations that flaunted elaborate finish work, for example the Witch of the Wave (185 1) interiors of “bird’s eye maple, with frames of satin wood, relieved with zebra, mahogany and rose wood, enamelled cornices edged with gold, and dark pilasters, with curiously carved and gilded capitals, and dark imitation marble pedestals” (Crothers 2000:435). By comparison, wives on whaleships retreated to their small deckhouse, which at only 6 ft. long, easily sat between mizzen and hatch (Figure 3).

On the Charles W. Morgan, the house measured 6 ft. x 6 ft., and about 6 ft. tall at the height of the arch in the roof and contained a fixed bunk on the starboard side, but otherwise little space for more than a chair. The door built in the aft side, fit to open on the port side of the mast and slid on rails across to starboard. A latch held it in place both open and closed. Photos of the old deckhouse show windows on each side, and no openings forward. The captain’s wife claimed this little deckhouse as her private retreat. Though she might have some say in the décor and furnishings of the sitting room below decks, her deckhouse would be her own to decorate. Mary Brewster wrote of her deckhouse in October 1847:

I have commenced regulating my apartments, which I like very much. I have no occasion to go below and I am entirely separate from the officers... Mr. Brewster and I take our meals at our own table and when seated we imagine we are keeping house. Here I am with my husband alone, and we are both making great calculations upon our enjoyment... (Brewster and Druett 1992:289)

Captain’s wives often generously gave up their space to the crew. Jamie Earle recounted that when a crewman fell from the rigging and broke a leg, his mother allowed the injured man to berth in her little deckhouse (Earle 1965). Though these cabins might be used by a woman on one voyage, on the next it might be converted to a rope locker or vegetable storage, so any investigation of gendered spaces on board requires studying them as a dynamic process, defined and negotiated through use (Hendon 2006).

Unfortunately, the deckhouse did not improve the situation enough for Clara and she departed for home in 1876, taking a steamer from St. Helena. She explained how she continually felt seasick, and stayed below decks in her cabin for days. “When the weather favored and I could get on deck, the smell of blubber and hens running about, and having to eat food made of sour dough made life offensive indeed” (f 1998:46).

Clara’s deckhouse was probably removed after the voyage. Years later in about 1887, while based in San Francisco, the shipyard records mentioned adding another deckhouse in the same spot on deck (Leavitt 1998). During the filming of “Down to the Sea in Ships” (1922), the museum removed the deckhouse (or a subsequent one), and unfortunately “lost” it. Shipwright Roger Hambidge at Mystic Seaport Shipyard, guesses the little house now functions as a shed in someone’s backyard in New Bedford. Where the house was once bolted thru the deck, the holes have been patched with tar and the wear pattern in the decking can still be seen. The wear from stepping through the door over the years created a low point in the deck planking. After the restoration of the whaleship Charles W. Morgan, the shipwrights did not return the deckhouse to its prior location, so the replica deckhouse remains in the shipyard.

Bathtubs

Honor Matthews met Captain James Earle in 1895 when he sailed into her hometown of Russell, New Zealand where she worked as a school teacher (Druett 2001: 125). In January 1896, they married in Honolulu and she sailed with him and their sons on several shorter voyages of about 11 months (Nov. to Oct.) out of San Francisco to the Northern whaling grounds (Leavitt 1998:60). During her voyaging, a bathtub existed in the captain’s cabin just forward of the head.

Bathing as a regular practice became acceptable in the 19th century, but the methods and forms of baths depended on availability. Women and men took sponge baths in basins, stepped into foot tubs, sat in sitz baths, or submerged in larger plunge tubs. In 1829, the Tremont Hotel in Boston became the first American building to include modern indoor plumbing matched with their luxury accommodations so guests could easily bathe with running water (Kaplan 2007). Until about 1860, only the extremely wealthy could afford water piped into their homes. Before that time, filling a portable tub required bucketing water heated on a stove. The Ladies’ and Gentlemen’s Etiquette Manual recommended daily bathing and a second bath or sponge bath before retiring in summer. In addition, “Once a week a warm bath, at about 100, may be used, with plenty of soap, in order to thoroughly cleanse the pores of the skin” (Duffey 1877:230).

At sea, fresh water required strict rationing, so those on board generally washed bodies (and clothes) with salt water, if they bothered to at all. The captain’s wives bathed when they could, though one wife mentioned her husband’s strict orders for only one bath a week even in a rainstorm when fresh water was accessible (Druett 2001:72). Tubs made of tin or brass would be more likely used on smaller ships, as the thick ceramic or iron tubs, such as those on the massive SS Great Britain, were very heavy. Although Jamie Earle (1965) describes the system of filling the tub on the whaleship Charles W. Morgan, he does not describe the tub itself beyond its location.

Their elder son, Jamie Earle lived with them on the Charles W. Morgan from 1902 to 1906, and he recalls the bathtub. The water tanks to fill it usually held sea water. “There were two tanks in the space back of the galley, one connected to a coil in the stove for hot water. These were filled with a hose and hand pump from the roof. I can remember one occasion when they were being filled with fresh water much to my mother’s delight.” Not just his mother used the tub, he continued, “I remember my father sitting in the tub with his head against the ceiling so it wasn’t very long or very deep...” (Earle 1965). Since then, the bathtub has been removed and there is now a counter with a wash basin in that location.

Conclusions

Even on identified shipwrecks with documented lists of crew on board, archaeology has the potential to find evidence of women not named on the records of the ship (Flatman 2003). If archaeologists discovered any of these large artifacts while investigating a 19th-century wreck, it might indicate a woman lived aboard and tells something of her story in regards to social structure and class. The gamming chairs and gimballed beds, women used specifically in a maritime context, and the bathtubs and parlor organs, they cherished as items from shore life. Deckhouses created a separate space for her apart from the lower class sailors.

Several factors need to be examined as to how definitive this evidence from large objects might be: some artifacts may have been left behind when a woman departed but possibly remained in use by the captain, other artifacts of feminine association may not have been used by the woman on board, and some artifacts may have been appropriated for other uses altogether. Finally, given the current lack of data or finds, it must be asked if archaeologists have been unable to identify these objects, or if the nature of the artifact and placement on the ship, create circumstances that render the artifacts unrecognizable or missing on most shipwrecks.

When women returned to life on shore, they left behind the heavy objects only useful on board and attached to the ship. Gamming chairs and gimballed beds had no use ashore. The chair might be kept aboard for use by visiting captain’s wives, despite no woman being in residence on the ship. The gimballed bed, bolted in place, remained in the captain’s cabin and so provided comfort for him. The bathtub probably stayed in place as long as the captain considered cleanliness a priority. It is not entirely a feminine object, but more an object delineating class distinctions, though wives aboard wrote of their joy to have one (Deblois 1856). Even if no woman sailed that voyage, the small deckhouse remained in location until removed by the ship’s carpenter or in the shipyard, after which it might get reuse as a garden shed. The parlor organ might be part of the ship’s cargo placed in the cabin, as was the one Hattie Atwood played on Charles Stewart in 1883 (Freeman and Dahl 1999). A woman who brought her organ on a voyage may have abandoned it, as Clara Tinkham did in 1876 when she left the Charles W. Morgan, but when the ship returned to port, the owner reclaimed her instrument (Willis 1876; Leavitt 1998:46). If the ship had sunk in any of these situations, the artifacts might indicate a woman living on board though she no longer resided there when it sank.

A woman on the ship might decide against using an object, such as Honor Earle refusing to use a gamming chair, so its presence on board might be deemed insignificant (Druett 2001). The artifacts might also be appropriated to another use such as the deckhouse could be transformed when the need arose, such as for medical emergencies, storage or even as a galley.

Jamie Earle (1965) recalls the small house becoming a galley on the Charles W. Morgan until they shifted it to the hurricane house. At any time, these objects may function in other uses, due to many factors, such as limited space aboard and the desires of the wife living on the ship.

Depending on site formation process, these objects might be recognized if intact, but if disintegrated, identification may be difficult while studying a shipwreck. Perhaps publishing of data and illustrations to inform and raise awareness among underwater archaeologists as to distinguishing features of these large artifacts may keep key pieces from being labelled ‘miscellaneous’ in site reports. The association of bed parts with a small pile of bricks or rocks may be unnoticed, but perhaps the additional support rods and pivot hinges would provide clues to identifying it as a gimballed bed. If a gamming chair made from a barrel survived the wrecking event, it could easily be mistaken for a broken barrel during the excavation. Although the songs are incorporeal, parts of the organ might be found, verifying the importance of music to those on board. The foot pedals and the bits of brass rods and arms, which allow the motions of bellows and keys, might last longer underwater than the thin wood paneling of organ housing.

The small deckhouse might be found if the deck remained intact, but more likely it would be missing along with the superstructure, such as that of the Two Brothers and other whaleship wrecks found off Hawaii in turbulent, tropical waters (NOAA 2010). As all of these wooden objects float and seem unlikely to be trapped under ballast, they may only be found underwater in perfect conditions, such as in a location like the Baltic with still, cold water and few shipworms (Muckelroy 1978; Bowens 2009). The bathtub, usually made of metal, may also disintegrate in an underwater environment, but situations exist in which it could survive, such as the tub on the shipwreck Titanic in the captain’s bathroom (Johnston 2003). The possibility exists for any one of these large artifacts to be found and provide data for gendered analysis of shipboard life.

If archaeologists found one (or even all) of these large artifacts, it still would not be definitive that a woman lived on the ship, but the inclusion of gendered hypotheses in the research design to accommodate for such finds would allow for further study. As research advances create a larger database, perhaps statistical modeling and structured taxonomies will permit a more specific analysis of how these objects could indicate gender in relation to class, race, and social structure in maritime archaeology.

Acknowledgments

My thanks goes to my thesis director, Dr. Lynn Harris, for her support with this study. I am grateful to ECU faculty and staff of the History department, Dr. Brad Rodgers, Dr. Karen Zipf, Calvin Mires, and Dr. Amy Mitchell-Cook of UWF for providing suggestions. I would like to thank the staff of the New England archives from Connecticut to Maine, and especially Mystic Seaport Museum where Charles W. Morgan docks. This research wouldn’t be possible without my work with NC Underwater Archaeology Branch, and the generosity of family and friends who continue to encourage me in this endeavor.

LMB-BML 2007 Webmaster & designer: Cmdt. André Jehaes - email andre.jehaes@lmb-bml.be